Scott M. Weissman, Steve Bleyl, Alan Rope, Jacob E. Berchuck, Jamie Esposito, Colleen Caleshu, Katie Kobara

Early-adopters of multi-cancer early detection testing often decline hereditary cancer genetic testing (CAN99)

Early-adopters of multi-cancer early detection testing often decline hereditary cancer genetic testing (CAN99)

Scott M. Weissman, Steve Bleyl, Alan Rope, Jacob E. Berchuck, Jamie Esposito, Colleen Caleshu, Katie Kobara

Background

Multi-cancer early detection (MCED), which detects cell-free tumor DNA for many different cancer types, became commercially available in 2021. Patients interested in MCED may also qualify for germline genetic testing (GGT), depending on their personal and family history of cancer. Little is known about testing uptake of MCED or uptake of GGT for those undergoing MCED. This is relevant as both tests provide patients information about their cancer risk.

Aim

We investigated test uptake and positivity rate for both MCED and GGT among a group of early adopters of MCED.

Methods

We performed a chart review of consecutive patients seen for pre-test genetic counseling (GC) regarding MCED between June 2021 & March 2022 as part of an employer benefit program. GC including a 3-generation pedigree was required to determine the patient’s eligibility for MCED within the program. If a patient met NCCN criteria for GGT, GGT was also offered. We extracted patient sex, age, personal cancer history, whether NCCN GGT criteria were met, and whether the patient opted to move forward with MCED and/or GGT. Two-sided t-tests were used to analyze uptake differences between the MCED and GGT among the patients that were offered GGT.

Results

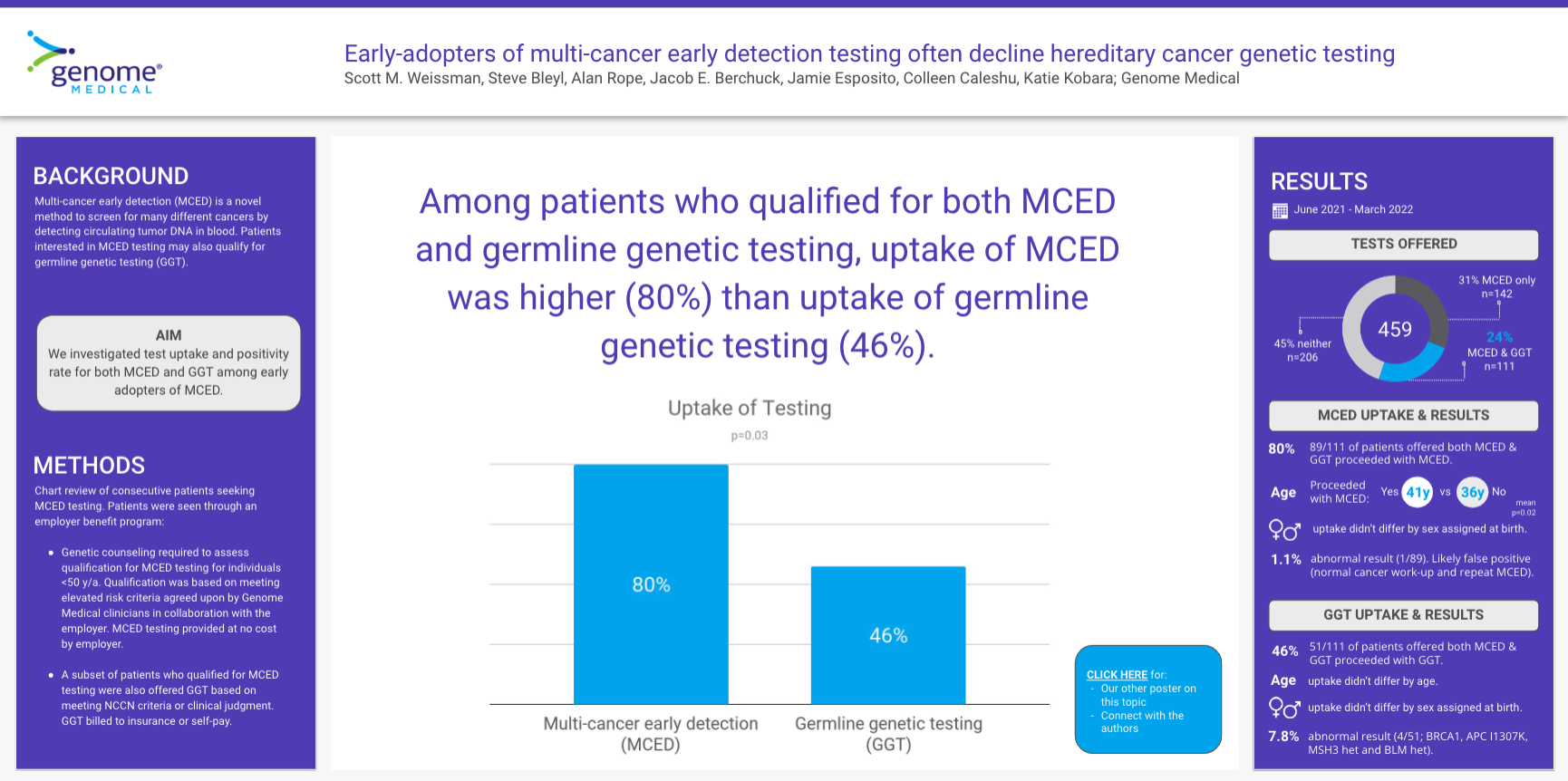

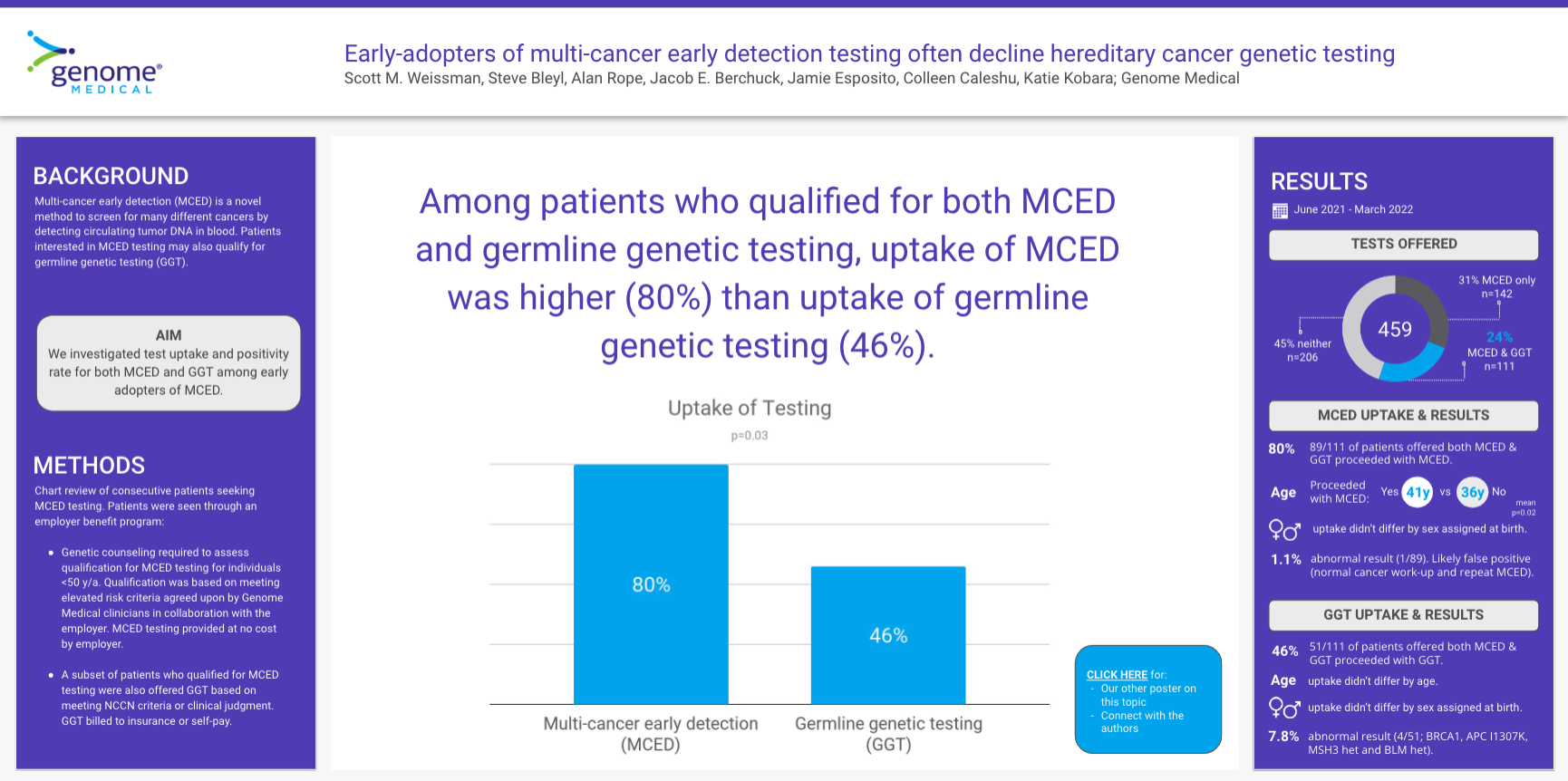

253 of 459 (55%) patients who presented for GC met criteria for MCED testing. Family history review showed 108/253 (43%) patients met NCCN criteria for GGT, all of whom were offered GGT. An additional 3 people were offered GGT based on clinical judgment or patient interest. In total, 111/253 (44%) patients were offered both MCED and GGT. Nearly all of those patients had no history of cancer (106/111, 95%). While the majority (89/111, 80%) opted for MCED, only 51/111 (46%) opted to pursue GGT (p=0.031). Patients opting for MCED were older than those who did not (41.2y v. 36.1y, p=0.015); no difference in MCED uptake was found between males and females. No differences were found in age or sex in uptake of GGT. The concordance between pursuing or declining both tests was 56% (62/111). The only positive MCED result was a likely false positive (2 Cancer Signals – uterine and ovarian cancers) (1/89, 1.1%). 4/51 (7.8%) additional patients had positive GGT.

Conclusion

Early adopters of MCED seemed more interested in understanding whether they had an undiagnosed, active cancer than a hereditary risk of developing cancer. Research is needed to understand the motives and decision-making of these patients as this information may help inform shared-decision making provided by genetic counselors and other clinicians.

Background

Multi-cancer early detection (MCED), which detects cell-free tumor DNA for many different cancer types, became commercially available in 2021. Patients interested in MCED may also qualify for germline genetic testing (GGT), depending on their personal and family history of cancer. Little is known about testing uptake of MCED or uptake of GGT for those undergoing MCED. This is relevant as both tests provide patients information about their cancer risk.

Aim

We investigated test uptake and positivity rate for both MCED and GGT among a group of early adopters of MCED.

Methods

We performed a chart review of consecutive patients seen for pre-test genetic counseling (GC) regarding MCED between June 2021 & March 2022 as part of an employer benefit program. GC including a 3-generation pedigree was required to determine the patient’s eligibility for MCED within the program. If a patient met NCCN criteria for GGT, GGT was also offered. We extracted patient sex, age, personal cancer history, whether NCCN GGT criteria were met, and whether the patient opted to move forward with MCED and/or GGT. Two-sided t-tests were used to analyze uptake differences between the MCED and GGT among the patients that were offered GGT.

Results

253 of 459 (55%) patients who presented for GC met criteria for MCED testing. Family history review showed 108/253 (43%) patients met NCCN criteria for GGT, all of whom were offered GGT. An additional 3 people were offered GGT based on clinical judgment or patient interest. In total, 111/253 (44%) patients were offered both MCED and GGT. Nearly all of those patients had no history of cancer (106/111, 95%). While the majority (89/111, 80%) opted for MCED, only 51/111 (46%) opted to pursue GGT (p=0.031). Patients opting for MCED were older than those who did not (41.2y v. 36.1y, p=0.015); no difference in MCED uptake was found between males and females. No differences were found in age or sex in uptake of GGT. The concordance between pursuing or declining both tests was 56% (62/111). The only positive MCED result was a likely false positive (2 Cancer Signals – uterine and ovarian cancers) (1/89, 1.1%). 4/51 (7.8%) additional patients had positive GGT.

Conclusion

Early adopters of MCED seemed more interested in understanding whether they had an undiagnosed, active cancer than a hereditary risk of developing cancer. Research is needed to understand the motives and decision-making of these patients as this information may help inform shared-decision making provided by genetic counselors and other clinicians.